How do Arctic terns undergo the world's longest migration?

Sterna paradisaea

The best human athletes who race long distances are often very tall and lanky. If you applied this logic to the bird world, you might think the best long-distance migrants would be cranes, herons, and flamingoes.

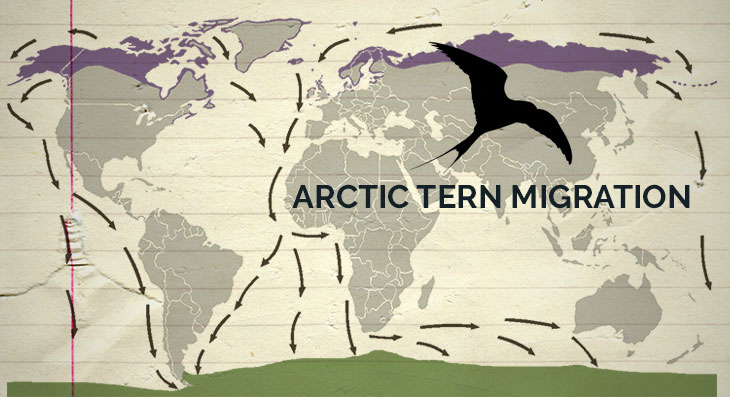

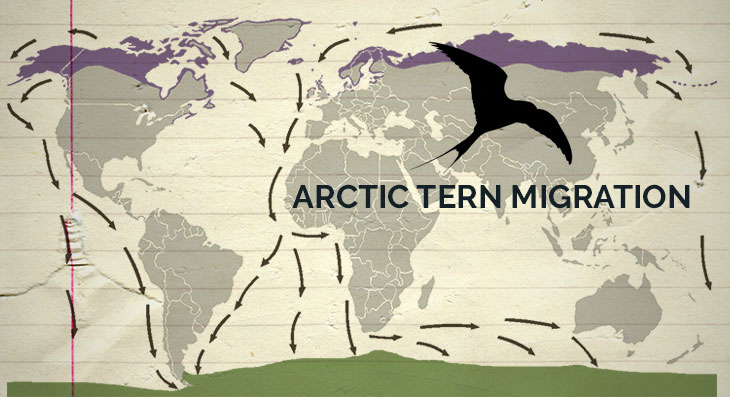

In fact, the prize for world’s farthest long-distance migrant belongs to the Arctic tern, a pint-sized little bird that weighs just about a quarter of a pound and has a wingspan of around two feet. This tiny bird migrates from Arctic breeding grounds to Antarctic feeding grounds and back, a round-trip distance of 44,000 miles – every year.

To understand why and how Arctic terns migrate so far, let’s tag along with them on their yearly journey.

Summer Breeding Grounds: May – August

A baby Arctic tern begins life somewhere in the Arctic regions around the world, either in North America, Europe, or Asia. They hatch in nests on the ground with up to two other siblings. While they seem like they’d be easy pickings for predators, Arctic tern parents are actually ferociously protective of their kids and will attack any size animal that comes too close – even people!

The tern’s parents feed it small fish, crustaceans, and zooplankton for the first month of its life before it leaves the nest. After that, they learn how to fly and eventually to dive into the water after their own food. Gradually, they’ll start feeding themselves so that they can grow and gain energy reserves in preparation for their first long migration – one of many to follow, if they’re lucky.

Fall Migration: August – November

Once it starts getting colder in the Arctic, they start making their way south and to the opposite end of the planet. Rather than flying in a straight line, though, they actually follow more of a pinball strategy. They tend to bounce around, even from continent to continent, while still generally heading south. Sometimes they’ll even stop in an area for up to a month to rest and refuel their energy reserves for their long migration.

Winter Feeding Grounds: November – April

Even though Arctic terns are born in Arctic regions, they actually spend the greatest part of the year in Antarctic regions. Here, they spend most of their time flying around the southern polar oceans bordering Antarctica, feasting on food.

Remember, even though it’s the winter season for those of us who live in the Northern hemisphere, it is the summer season for the southern hemisphere. All of the bountiful food that the terns found in the Arctic summer areas is now present here, too, and the terns spend the whole time pigging out on the all-you-can-eat buffet. By migrating, they effectively avoid winter entirely and live in perpetual summer with an endless smorgasbord of food!

Spring Migration: April – May

When it starts getting cold in the Antarctic region, the terns begin heading north again. This time, rather than pretending they’re pinballs, they fly a much more direct route back to the north and arrive within a month’s time.

How are Arctic terns able to migrate so far?

Arctic terns are able to complete these amazing feats thanks to several behavioral and physiological adaptations. Just like Goldilocks and her bed, these birds are just the right size – not too small and not too big. They’re large enough to carry adequate energy reserves to get them through their long migration, but not too big as to be too energetically expensive to fly. They also take advantage of wind currents to blow them the direction they want to go. By doing so, they spend most of their time just gliding on the currents rather than flapping the whole way. They also take advantage of pit stops to rest and refuel, just like long-distance racers.

To date, the oldest Arctic tern found lived to be 34. If it migrated on average 44,000 miles each year, this bird would have flown just shy of 1.5 million miles in its lifetime – enough for three trips to the moon and back! So the next time you get on an airplane and fly somewhere, imagine what it would be like to rack up airline miles as an Arctic tern!

Related Topics

The best human athletes who race long distances are often very tall and lanky. If you applied this logic to the bird world, you might think the best long-distance migrants would be cranes, herons, and flamingoes.

In fact, the prize for world’s farthest long-distance migrant belongs to the Arctic tern, a pint-sized little bird that weighs just about a quarter of a pound and has a wingspan of around two feet. This tiny bird migrates from Arctic breeding grounds to Antarctic feeding grounds and back, a round-trip distance of 44,000 miles – every year.

To understand why and how Arctic terns migrate so far, let’s tag along with them on their yearly journey.

Summer Breeding Grounds: May – August

A baby Arctic tern begins life somewhere in the Arctic regions around the world, either in North America, Europe, or Asia. They hatch in nests on the ground with up to two other siblings. While they seem like they’d be easy pickings for predators, Arctic tern parents are actually ferociously protective of their kids and will attack any size animal that comes too close – even people!

The tern’s parents feed it small fish, crustaceans, and zooplankton for the first month of its life before it leaves the nest. After that, they learn how to fly and eventually to dive into the water after their own food. Gradually, they’ll start feeding themselves so that they can grow and gain energy reserves in preparation for their first long migration – one of many to follow, if they’re lucky.

Fall Migration: August – November

Once it starts getting colder in the Arctic, they start making their way south and to the opposite end of the planet. Rather than flying in a straight line, though, they actually follow more of a pinball strategy. They tend to bounce around, even from continent to continent, while still generally heading south. Sometimes they’ll even stop in an area for up to a month to rest and refuel their energy reserves for their long migration.

Winter Feeding Grounds: November – April

Even though Arctic terns are born in Arctic regions, they actually spend the greatest part of the year in Antarctic regions. Here, they spend most of their time flying around the southern polar oceans bordering Antarctica, feasting on food.

Remember, even though it’s the winter season for those of us who live in the Northern hemisphere, it is the summer season for the southern hemisphere. All of the bountiful food that the terns found in the Arctic summer areas is now present here, too, and the terns spend the whole time pigging out on the all-you-can-eat buffet. By migrating, they effectively avoid winter entirely and live in perpetual summer with an endless smorgasbord of food!

Spring Migration: April – May

When it starts getting cold in the Antarctic region, the terns begin heading north again. This time, rather than pretending they’re pinballs, they fly a much more direct route back to the north and arrive within a month’s time.

How are Arctic terns able to migrate so far?

Arctic terns are able to complete these amazing feats thanks to several behavioral and physiological adaptations. Just like Goldilocks and her bed, these birds are just the right size – not too small and not too big. They’re large enough to carry adequate energy reserves to get them through their long migration, but not too big as to be too energetically expensive to fly. They also take advantage of wind currents to blow them the direction they want to go. By doing so, they spend most of their time just gliding on the currents rather than flapping the whole way. They also take advantage of pit stops to rest and refuel, just like long-distance racers.

To date, the oldest Arctic tern found lived to be 34. If it migrated on average 44,000 miles each year, this bird would have flown just shy of 1.5 million miles in its lifetime – enough for three trips to the moon and back! So the next time you get on an airplane and fly somewhere, imagine what it would be like to rack up airline miles as an Arctic tern!